There is a strong thematic unity between the teachings of the great French ethnologist Marcel Mauss and the work of the so-called 'philosopher of evil', Georges Bataille. This is the third in a short series of posts in which I take up the relations between the writings of the two men.

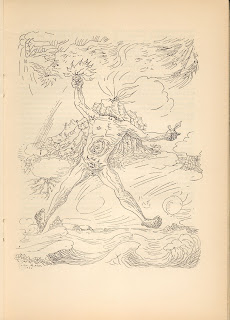

There is a strong thematic unity between the teachings of the great French ethnologist Marcel Mauss and the work of the so-called 'philosopher of evil', Georges Bataille. This is the third in a short series of posts in which I take up the relations between the writings of the two men.In 1936 Georges Bataille created a secret society called "Acéphale" - Headless. Members were Georges Ambrosino, Pierre Klossowski, Patrick Waldberg. Probable members were Michel Leiris, Jacques Chavy (a sociologist, translator of Max Weber), René Chenon, Henri Dubief (a historian), Pierre Dugan, Dussat, Jean Dautry and Colette Peignot. Whether Roger Caillois was a member is disputed. Jacques Lacan was aware of Acéphale's existence and purposes, but in all probability not a member.

It was a hierarchical society, into which one one was ritually initiated and which knew ranks or grades. All members were sworn to secrecy.

The interbellum, and specifically Weimar Germany, was rife with 'secret societies of political assassins' (Caillois). Nonetheless, Acéphale was probably not intended to mimic the terrorist associations of 'Secret Germany'. The idea of forming a secret society for sociological action seems to have been inspired largely by Marcel Mauss's work on conspiracies. Mauss had been lecturing on that theme for some time and in 1936 had wanted to compose a text about it for the journal "Cahiers du Socialiste". "The ethnologist was well aware of the 'significant role' of 'men's organizations' in societies of the archaic type: 'secret brotherhoods very effectively ensure social stability,' he wrote. He was preoccupied at the time with the idea of 'secrecy and plotting' in politics. Following a paper delivered by Élie Halévy on 'the age of tyrannies' before members of the Société Française de Philosophie, he returned to it: 'I stress the fundamental fact of secrecy and plotting more than you do. ... Even sociologically, it may be a necessary form of action, but it is a backward form. That is no reason for it not to be fashionable. It satisfies the need for secrecy, influence, action, youth, and often tradition" (Fournier).

Acéphale's members observed particular customs and rituals. "The most important and best-known (...) remains the one by which members traveled separately by train from Saint-Lazare station to the tiny station of Saint-Nom-La-Bretèche, strangely lost in the midst of a forest, and from there, at night, alone and in silence, proceeded to the foot of a tree struck by lightning (...). There they burnt sulphur, and that is about all we know". On the 21st of January they commemorated the beheading of Louis XVI on the Place De La Concorde. "The Place De La Concorde is the place were the death of God has to be announced and proclaimed because its obelisk is the calmest negation of it". There were culinary rituals: the daily lunch was to be composed of horsemeat washed down with water (wine was tabooed during the day). Furthermore, Acéphale established moral rules: it was forbidden to shake hands with anti-Semites. No doubt these 'invented traditions' were inspired by Bataille's ethnographic reading.

Acéphale however is most notorious for a ritual that was never performed (appropriate perhaps for a headless society not to perform it's main rite). Acéphale's ultimate goal was to enact a sacrifice of one of it's members. "There was another idea, hatched by Bataille, that the action of a group could be fully efficacious only if the initial pact of alliance among it's members was truly irremediable. And he was convinced that to bind their energies together, it was necessary to perform a human sacrifice. (...) I am not at all sure what transpired with regard to this projected human sacrifice. What is clear, though, is that it was easier to find a volunteer victim than a sacrificer, and so things went no further" (Caillois). But Acéphale's ambitions went further than a mere Dostoevsky-inspired scheme to solidify the loyalty to each other by murdering one of their fellow conspirators. The activities of Acéphale were directed towards society as a whole. Through the mediation of the sacrificial victim a means of communication would be established through not only between the members of the secret society, but also with society. Social life would be stimulated and society reinvigorated and thereby saved from fascism. Thus, Acéphale was acting upon Mauss's work on sacrifice; Acéphale was applied ethnology.

Acéphale however is most notorious for a ritual that was never performed (appropriate perhaps for a headless society not to perform it's main rite). Acéphale's ultimate goal was to enact a sacrifice of one of it's members. "There was another idea, hatched by Bataille, that the action of a group could be fully efficacious only if the initial pact of alliance among it's members was truly irremediable. And he was convinced that to bind their energies together, it was necessary to perform a human sacrifice. (...) I am not at all sure what transpired with regard to this projected human sacrifice. What is clear, though, is that it was easier to find a volunteer victim than a sacrificer, and so things went no further" (Caillois). But Acéphale's ambitions went further than a mere Dostoevsky-inspired scheme to solidify the loyalty to each other by murdering one of their fellow conspirators. The activities of Acéphale were directed towards society as a whole. Through the mediation of the sacrificial victim a means of communication would be established through not only between the members of the secret society, but also with society. Social life would be stimulated and society reinvigorated and thereby saved from fascism. Thus, Acéphale was acting upon Mauss's work on sacrifice; Acéphale was applied ethnology.Bataille: "I had spent the preceding years with an unsupportable preoccupation: I was resolved, if not to found a religion, at least to direct myself towards this meaning. What the history of religions had revealed to me had gradually exalted me". And who was France's preeminent historian of religions, the president of the Section of Religious Science at the École pratique des hautes études, with whose work Bataille was intimately familiar? Mauss!

Mauss, through himself probably unaware of Acéphale, was highly critical of the anti-rational tendencies of Bataille's coterie. In a 1938 letter to Roger Caillois on the latter's essay "Paris, mythe moderne" in "Le mythe et l'homme" he wrote :

"What I believe is a general derailment - of which you are a victim - is the sort of absolute irrationalism with which you conclude in the name of a modern myth (...). But I believe that, right now, all of you are probably under the influence of Heidegger, a Bergsonian held back by Hitlerism, legitimating a Hitlerism infatuated with irrationalism. And above all, it's the political philosophy of sorts you try to draw from it, in the name of poetry and vague sentimentality. As persuaded as I am that poets and men of great eloquence can sometimes establish the rhythms of social life, so too am I skeptical of the capacities of the philosophy of any kind (...) to establish the rhythm of anything at all." (quoted in Fournier's book).

Bataille, for a variety of reasons, would come to abandon the attempt to found a religion based on Maussian theory when the war broke out. That did not end his fascination for Mauss's analysis of sacrifice, however. In the war, he would examine the meaning of sacrifice in a world whose God is dead more rigorously than in the Acéphale period. I'll examine this development in Bataille's thinking in an upcoming post.

Post scriptum

Here is a link to an issue of the journal Acéphale.

This French-language pdf contains a biograhical essay on Patrick Waldberg.

Is Acéphale's René Chenon the same man as this mathematics professor (link)?

Was Georges Ambrosino the author of this 1960 book on nuclear physics?

Information on Acéphale's Henri Dubief: "Henri Dubief (1910-1995), agrégé d'histoire, fut inspecteur général de l'Instruction publique, vice-président de la Société d'histoire du protestantisme français, auteur de La Réforme (Rencontre, 1965), La Réforme et la littérature française (La Cause, 1972), de divers ouvrages historiques et de collaborations à des revues scientifiques". Amazing that someone involved in a conspiracy directed towards human sacrifice could become inspector-general for public education!

4 comments:

This is really fascinating; I was wholly unaware of this strain of social thought, but I'll definitely be researching it more deeply now. Thanks!

Yes, Ambrosino was the nuclear scientist. He's also thanked in the preface to Le part maudite as being an important contributor to its ideas.

As for your whole blog triptych on this: WOW!

You should read "Sacred Revolutions" by Michele Richman. Clearly contextualizes Bataille's thinking/experiments (including acephale) in the late 1930s within the Durkheim/Mauss legacy.

Thanks for the nice comments and the interesting information!

Post a Comment