This final episode of a short series of posts which features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success. Blood on Satan's Claw is one of my favorite horror films.

Blood on Satan's Claw (Piers Haggard, 1971)

Doomwatch (Peter Sasdy, 1972)

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Monday, April 27, 2009

Xasthur - All Reflections Drained

"Nothing is beautiful, except man alone: all aesthetics rests upon this naïveté, which is its first truth. Let us immediately add the second: nothing is ugly except the degenerating man — and with this the realm of aesthetic judgment is circumscribed. Physiologically, everything ugly weakens and saddens man. It reminds him of decay, danger, impotence; it actually deprives him of strength. One can measure the effect of the ugly with a dynamometer. Wherever man is depressed at all, he senses the proximity of something "ugly." His feeling of power, his will to power, his courage, his pride — all fall with the ugly and rise with the beautiful. In both cases we draw an inference: the premises for it are piled up in the greatest abundance in instinct. The ugly is understood as a sign and symptom of degeneration: whatever reminds us in the least of degeneration causes in us the judgment of "ugly." Every suggestion of exhaustion, of heaviness, of age, of weariness; every kind of lack of freedom, such as cramps, such as paralysis; and above all, the smell, the color, the form of dissolution, of decomposition — even in the ultimate attenuation into a symbol — all evoke the same reaction, the value judgment, "ugly." A hatred is aroused — but whom does man hate then? There is no doubt: the decline of his type. Here he hates out of the deepest instinct of the species; in this hatred there is a shudder, caution, depth, farsightedness — it is the deepest hatred there is. It is because of this that art is deep."

"Nothing is beautiful, except man alone: all aesthetics rests upon this naïveté, which is its first truth. Let us immediately add the second: nothing is ugly except the degenerating man — and with this the realm of aesthetic judgment is circumscribed. Physiologically, everything ugly weakens and saddens man. It reminds him of decay, danger, impotence; it actually deprives him of strength. One can measure the effect of the ugly with a dynamometer. Wherever man is depressed at all, he senses the proximity of something "ugly." His feeling of power, his will to power, his courage, his pride — all fall with the ugly and rise with the beautiful. In both cases we draw an inference: the premises for it are piled up in the greatest abundance in instinct. The ugly is understood as a sign and symptom of degeneration: whatever reminds us in the least of degeneration causes in us the judgment of "ugly." Every suggestion of exhaustion, of heaviness, of age, of weariness; every kind of lack of freedom, such as cramps, such as paralysis; and above all, the smell, the color, the form of dissolution, of decomposition — even in the ultimate attenuation into a symbol — all evoke the same reaction, the value judgment, "ugly." A hatred is aroused — but whom does man hate then? There is no doubt: the decline of his type. Here he hates out of the deepest instinct of the species; in this hatred there is a shudder, caution, depth, farsightedness — it is the deepest hatred there is. It is because of this that art is deep."F.W. Nietzsche - Twilight of the Idols (1895)

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Shock Xpress - Home Grown British Crud (pt. 7)

This short series of posts features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success.

The Haunted House of Horror (Michael Armstrong, 1969)

Zeta One (Michael Cort, 1969)

The Haunted House of Horror (Michael Armstrong, 1969)

Zeta One (Michael Cort, 1969)

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Alice Coltrane - Lord of Lords

"228. Against mediators. - Those who want to mediate between two resolute thinkers show that they are mediocre; they lack eyes for seeing what is unique. Seeing things as similar and making things the same is the sign of weak eyes." Friedrich Nietzche, The Gay Science.

"228. Against mediators. - Those who want to mediate between two resolute thinkers show that they are mediocre; they lack eyes for seeing what is unique. Seeing things as similar and making things the same is the sign of weak eyes." Friedrich Nietzche, The Gay Science.Alice Coltrane had weak eyes. Her 1972 album Lord of Lords was her third and final album for the Impulse! label. The music on the album was made to match her New Age spirituality - a spirituality which sought the universal, which was "...determined to deny that which opposes the sannyasi to the Roman prelate, or the Sufi to the Kierkegaardian pastor..." (Bataille). The insipid mediocrity of her beliefs carried over into her music, which attempted to mediate Jazz, Western Classical music, Indian Classical Music, Delta Blues, Gospel. The result can be heard as a synthesis which is so sentimental and saccharine, that it positively cloys.

Alice Coltrane had weak eyes. She did not see that her New Age spirituality was servile. Her search for deliverance, salvation, and possession of the 'supreme goal of life', expressed the will to straitjacket herself within an authoritarian religious ideal. At the time of the making of 'Lord of Lords' the religious authority was that of Swami Satchidananda; and after that Swami's death, the religious authority was that of the controversial South Indian guru Sathya Sai Baba. Called 'a divine being and a sacred embodiment' on the website of Alice Coltrane's own Vedantic temple, this guru deified himself in order to sexually abuse young followers. The authoritarian aspect of Alice Coltrane's spirituality also carried over into her musical praxis. The title of the album itself refers to authority. Furthermore, I see her work as the continuation of nineteenth-century Western Classical Music, in which the composer was viewed as an artist-prophet, as a spiritual authority, while the orchestra musician was passive, a servile follower of the dictates of composer. With the central track titled 'Excerpts from The Firebird', Alice Coltrane places 'Lord of Lords' squarely in this Western Classical Music tradition. On the album as a whole, improvisation is at a minimum; Alice Coltrane leads a 16-piece string orchestra as an artist-prophet, with only herself, bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Ben Riley being allowed some improvisatory freedom.

Alice Coltrane may have had weak eyes - but what if we listen to her music with sharp ears?

Listening to the album with sharp ears, we can hear the music in many different ways.

We can attempt to discern the various musical strata of 'Lord of Lords', we can try to differentiate between Jazz, Western Classical music, Indian Classical Music, Delta Blues and Gospel, we can seek multiplicity in the synthesis, we can try to find forms in the universal. Here, we break down the unified into a plethora of significant unities. We hear many unique things, and marvel at the luminescent abysses that divide and connect them. Listening with sharp ears, we make things different again.

We can employ another listening technique and desublimate the universal into formlessness. When we listen this way, the corniness of her spirituality becomes a pleasurable infraction of the laws of good taste. The celestial character of the harps and violins only serves to underscore the feverish lowness of the drones. Instead of ascending to the heavens, we descend into compository chaos. The Firebird falls into the Icarian Sea. Free Jazz, Western Classical music, Indian Classical Music, Delta Blues and Gospel all collapse. Drones drown compositions. The saccharine melts and becomes syrupy. 'Lord of Lords' turns out to be fascinating; something that cannot be tamed by any concept. Listening with sharp ears, we hear the measureless and incomparable.

We can employ another listening technique and desublimate the universal into formlessness. When we listen this way, the corniness of her spirituality becomes a pleasurable infraction of the laws of good taste. The celestial character of the harps and violins only serves to underscore the feverish lowness of the drones. Instead of ascending to the heavens, we descend into compository chaos. The Firebird falls into the Icarian Sea. Free Jazz, Western Classical music, Indian Classical Music, Delta Blues and Gospel all collapse. Drones drown compositions. The saccharine melts and becomes syrupy. 'Lord of Lords' turns out to be fascinating; something that cannot be tamed by any concept. Listening with sharp ears, we hear the measureless and incomparable.Those who hear only the universal in Alice Coltrane's music show that they are mediocre; they lack eyes for seeing what is heterogeneous in her work. Hearing her music as a synthesis and reducing her music to universal nature is the sign of weak ears.

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Shock Xpress - Home Grown British Crud (pt. 6)

This short series of posts features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success.

The Sorcerers (Michael Reeves, 1967)

Curse of the Crimson Altar (Vernon Sewell, 1968)

The Sorcerers (Michael Reeves, 1967)

Curse of the Crimson Altar (Vernon Sewell, 1968)

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Ballard Is Dead

From an interview with J.G. Ballard, by Graeme Revell:

From an interview with J.G. Ballard, by Graeme Revell:"JGB: Actually, whereas classical mythologies, classical legends, tended to be concerned with explaining origins (where the world came from, how the planets were formed, how life itself was born), I think the sort of mythologies I'm interested in (in, say, Myths of the Near Future) are concerned with ends rather than with beginnings. Certainly they're projections. The title Myths of the Near Future exactly sums up what I think a lot of present writers, musicians like yourself (as far as I can tell), filmmakers, painters like, say, Francis Bacon, are concerned with: the mythologies of the future. Not myths which will one day replace the classical legends of ancient Greece, but predictive mythologies; those which in a sense provide an operating formula by which we can deal with our passage through consciousness - our movements through time and space. These are mythologies you can actually live by: how to cope with the urban landscape, the whole series of enciphered meanings that lie half-exposed within the urban landscape, within the communications landscape we all inhibit and to some extent contribute to. I'm interested in what I think of as a radically new set of mythologies that aren't concerned with the past, even in the sense that psychoanalysis is concerned with the past...".

J.G. Ballard, our Euripides, has passed away...

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Dominic Fox - Cold World

Cold World

Cold WorldDominic Fox

978-1-84694-217-4

Price: $14.95 / £7.99

Date of publication: 25 September 2009

To live well in the world one must be able to enjoy it: to love, Freud says, and work. Dejection is the state of being in which such enjoyment is no longer possible. There is an aesthetic dimension to dejection, in which the world appears in a new light. In this book, the dark serenity of dejection is examined through a study of the poetry of Hopkins and Coleridge, and the music of "depressive" black metal artists such as Burzum and Xasthur.

The author then develops a theory of "militant dysphoria" via an analysis of the writings of the Red Army Fraction's activist-theoretician, Ulrike Meinhof. The book argues that the "cold world" of dejection is one in which new creative and political possibilities, as well as dangers, can arise. It is not enough to live well in the world: one must also be able to affirm that another world is possible.

Dominic kindly sent me a preview of his fascinating book, which touches on many of the themes discussed in this blog. Specifically, the ways Dominic relates RAF terrorism to the militancy of the early Black Metal scene inspired this post on Sorel and Black Metal. I intend to post a full review of the book come summer.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Shock Xpress - Home Grown British Crud (pt. 5)

This short series of posts features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success.

Witchfinder General (Michael Reeves, 1968)

Incense for the Damned (Robert Hartford-Davis, 1970)

Witchfinder General (Michael Reeves, 1968)

Incense for the Damned (Robert Hartford-Davis, 1970)

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Roger Andersson- Letters From Mayhem

Found references to a 2004 art book titled 'Letters From Mayhem' by Swedish artist Roger Andersson, while researching the previous post. The book, published by Cabinet, consists of illustrations incorporating each letter of the alphabet within an imaginary landscape of Scandinavian flora, discarded packaging and anonymous 'youths' - somewhere between wasteland and wonderland. Thr illustrations are accompanied by a fragmentary text by poet Albert Mobilio.

Found references to a 2004 art book titled 'Letters From Mayhem' by Swedish artist Roger Andersson, while researching the previous post. The book, published by Cabinet, consists of illustrations incorporating each letter of the alphabet within an imaginary landscape of Scandinavian flora, discarded packaging and anonymous 'youths' - somewhere between wasteland and wonderland. Thr illustrations are accompanied by a fragmentary text by poet Albert Mobilio.The 'Mayhem' in the book's title is indeed a reference to the Black Metal band which has featured so much on this blog.

Here is a link to a translated page of the Magnus Karlsson Gallery, where Andersson exhibited his work.

Here is a link to a rather critical review in the Irish art magazine Circa.

Monday, April 13, 2009

Euronymous's Epistles

Øystein "Euronymous" Aarseth was an epistolary enthusiast. As Bård G. "Faust" Eithun reminisces in a 2005 article on Norwegian Black Metal in the Guardian, 'Any correspondence with Euronymous quickly escalated into very long letters...'. Jørn "Necrobutcher" Stubberud in the same article: 'While I was out raising hell with all my drug friends, he was home writing letters.'

Øystein "Euronymous" Aarseth was an epistolary enthusiast. As Bård G. "Faust" Eithun reminisces in a 2005 article on Norwegian Black Metal in the Guardian, 'Any correspondence with Euronymous quickly escalated into very long letters...'. Jørn "Necrobutcher" Stubberud in the same article: 'While I was out raising hell with all my drug friends, he was home writing letters.'The photograph reproduced nearby suggests that his letters were extravagant, theatrical creations which must have cost a lot of time to produce - especially since they were written before the widespread use of word processing applications.

I should very much like to write about Euronymous's letter-writing. For this reason, I call upon the readership of this blog to send scanned versions of any of his letters to surrealdocuments [at] hotmail.com.

Saturday, April 11, 2009

Georges Sorel - Reflections On Violence (pt. 3)

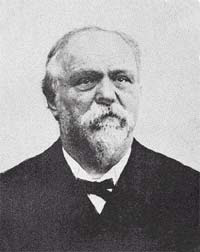

In the third and final of this short series of posts on revolutionary firebrand Georges Sorel, I examine the relations between his work and that of the father of modern ethnology, Marcel Mauss. The relation between the two is relevant, because Georges Sorel's belief in the need for a deliberately-conceived "myth" to sway crowds into concerted action was inspired by contemporary ethnology and sociology, and specifically by the works of Marcel Mauss's uncle Émile Durkheim.

In the third and final of this short series of posts on revolutionary firebrand Georges Sorel, I examine the relations between his work and that of the father of modern ethnology, Marcel Mauss. The relation between the two is relevant, because Georges Sorel's belief in the need for a deliberately-conceived "myth" to sway crowds into concerted action was inspired by contemporary ethnology and sociology, and specifically by the works of Marcel Mauss's uncle Émile Durkheim.Moreover, not only were both Sorel and Mauss active militant Socialists, they were acqainted personally. The revolutionary and the ethnographer and attended classes together at the Sorbonne in 1895. At the time, Mauss was 23; Sorel was 58 and already retired. Mauss described Sorel as "an older comrade, an astute critic of everything but himself."

Even if Durkheim and Mauss were Leftists, they were not Marxists. Nonetheless, Sorel saw in Durkheim a potential ally. In April and May 1895, in the first two issues of Devenir Social (an international journal of economics, history and philosophy published in Paris),

"...Sorel published a long article titled 'Mr. Durkheim's Theories". At the time, Mauss thought Sorel had 'a penetrating mind, if not a learned and judicious one.' Against the 'babblers who rant on about social questions,' Mauss was to side with the '(overly) scientific minds.' The tone of Sorel's articles was respectful, except when he evaluated the political ideas of the author of The Rules of Sociological Method and The Division of Labour in Society: 'The author takes a forceful stand against socialism. He maintains that all the research done heretofore on value is not truly scientific. ... One must not conceal that socialism is facing an adversary of the first order.' This criticism did not prevent Sorel from inviting Durkheim to 'embrace socialism': 'Perhaps he will manage to cross the line separating him from us: it would be a happy event for social philosophy; I would be the first to acclaim him as my master. No scientist is better prepared than he to bring Marx's theories to higher education'." (sourced here)

But around 1904-1905, when revolutionary anarcho-syndicalism developed, the relationship between Sorel and the French sociologists cooled down considerably. Georges Sorel, Mauss wrote, "vents his filthy bile on his best friends, on the people he respects most." In 1906, Georges Sorel published a series of articles in the magazine Le Mouvement Socialiste. These articles appeared in book form as Reflections on Violence in 1908. The rift between Sorel and Durkheim's sociological school is made abundantly clear by the many disparaging remarks on sociologists in Reflections on Violence. Nevertheless, Sorel's book proves that the revolutionary was still actively following Durkheim's work, as it refers to a 1906 lecture by the sociologist.

But around 1904-1905, when revolutionary anarcho-syndicalism developed, the relationship between Sorel and the French sociologists cooled down considerably. Georges Sorel, Mauss wrote, "vents his filthy bile on his best friends, on the people he respects most." In 1906, Georges Sorel published a series of articles in the magazine Le Mouvement Socialiste. These articles appeared in book form as Reflections on Violence in 1908. The rift between Sorel and Durkheim's sociological school is made abundantly clear by the many disparaging remarks on sociologists in Reflections on Violence. Nevertheless, Sorel's book proves that the revolutionary was still actively following Durkheim's work, as it refers to a 1906 lecture by the sociologist.Eight years later, the First World War broke out. From Edward A. Shils' excellent introduction: "The First World War horrified [Georges Sorel], not because it was a war, but because it was fought by the Entente in the name of democracy, and because it was conducted on such a large bureacucratic scale that the heroism of a small group seemed impossible. The Russian Revolution raised his hopes again, and he thought to see in the Bolshevik party the small zealous elite of heroic warriors who would precipitate the great moral transformation of human society for which he always lived. He died in 1922, a little before the March on Rome by his Italian admirers and their barbarous cohorts, and before the Russian Revolution had settled into a repellent routine. For him, the apocalypse seemed imminent."

Marcel Mauss volunteered for the duration of the war on September 3, 1914, serving in the trenches as an interpreter. Many of Mauss's close friends died in the war, including the ethnographer Robert Hertz. After Émile Durkheim's son André was killed in action op December 18, 1915, Durkheim suffered from severe depressions and finally died from grief on November 15, 1917. It was a a harrowing time. When the Russian Revolution broke out, Mauss initially supported the overthrow of the Russian aristocracy. However, he did not share the delirious enthusiasm of his Socialist comrades. In 1921 Mauss wrote ironically: "The comrades have wanted to join with Moscow go there as if on a pilgrimage. They are moved by an act of faith. For them, it's like the star rising in the east. They are guided by the star. Christ is born. Socialism has become a reality in Russia: Bethlehem is Moscow."

"In 1923, Mauss published a series of five long article in [the political weekly] Vie Socialiste called 'Observations on Violence'. Why had Russia been swept away by a 'sort of mass hysteria'? Mauss sought to understand the Russian people, who had been 'fiercely boycotted by almost the entire world,' and who were not 'isolated, starving, bankrupt, deserted by most of their best elements.' The (historical and sociological) explanation was simple: here was a country that, like Italy, was 'poor, backward and unlucky.' According to Mauss, the tyranny developing there was proof of 'the political incompetence of this people'. Bolshevism and Fascism attested to the 'regression' of modern societies; they were 'political episodes in the life of politically uneducated peoples.' Because there was no public opinion, the political realm was left to 'activist minorities'. It was therefore not surprising that the 'Kremlin brutes' with their 'adventuristic practices' had prevailed.In 1925 Marcel Mauss published an article, "A sociological assessment of Bolshevism", in which he held Sorel responsible for Bolshevik misdeeds:

Mauss's series of articles, subtitled 'Fascism and Bolshevism,' was presented as a response to George Sorel's Reflections on Violence, which had been published in 1908. Mauss was not unhappy to engage in a polemic with his old comrade, whom he had met in 1895 and whom he presented as 'an embittered old man with no concern for the consequences of his acts, with no mandate, and with no scientific scruples.' Sorel had become the apostle of violence and 'direct action,' announcing the 'victory of minorities over majorities.' For Mauss, it was particularly important to criticize that 'ideology of so-called realists,' because he considered Sorel to be Lenin's and Mussolini's 'sponsor'. But beyond polemics, what Mauss wanted was to better understand the Bolshevik Revolution, certain aspects of which he had already harshly criticized in Populaire [the organ of the SFIO). His diagnosis was merciless. Of course, 'certain claims to glory' and 'a few benefits' of the Bolshevik Revolution could be identified: it had destroyed the bureaucracy and the Russian aristocracy, had ushered in federalism, had emancipated 'a few tyrannized populations,' and had returned land to the peasants after 'a few years of abberation'. But on the whole, the liabilities were 'awful'.

For Mauss, Bolshevism would be known for 'the poverty of ideas and of its legal and administrative accomplishments.' What was his criticism of the Russian communists? First, they believed 'that it is possible to establish laws and rights by decree, by violence, that it is possible to oversee various interests without the consent and confidence of the interested parties.' Second, they had 'destroyed everything' in the economy, had abolished all private commerce, had eliminated all markets, all stock exchanges, all speculation. Third, an even worse, they had 'dried up the very source of any social life: confidence and good faith.' Finally, they had waged social revolution 'against the most active classes in the country, against the institutions most dear to it and those that would be most essential to its success.' For Mauss, this was a historical paradox: 'In Moscow, the dictatorship of the proletariat has become the dictatorship of the Communist Party over the proletariat.'

A defender of the doctrine of 'activist majorities', Mauss condemned violence. In Russia and Italy, it was 'pointless and mad.' From his standpoint, the best administration was one that was least intrusive. 'In our nations, the more mighty a regime, the less it needs to use its might.' (sourced from Marcel Fournier's excellent biography of Marcel Mauss)

"Elsewhere I have set out at length the observations that can be drawn from the systematic use that the Bolsheviks have made of violence. All I have to add to this here is to note its failure. The Communists, here followers of Georges Sorel, have turned it into a true political 'myth', an article of faith. Not only does the whole Third International regard it as the revolutionary means pas excellence; not only do the Communists advocate it as the means of conclusively establishing the Revolution that has already been made and of applying the laws laid down by a dictator proletariat, it has also become for them a kind of end in itself. They have set up a kind of fetish figure in honor of force, the 'midwife of societies' (Marx). As the Communists seized power violently, as anyway it was always part of the Bolshevik programme and not an improvisation, they have made the excersice of violence the infallible sign of proletarian power and of the Revolution. They only recognize Communism where they see violence and terror." (sourced here)

Post scriptum

For The Great Baarsini.

Thursday, April 09, 2009

Shock Xpress - Home Grown British Crud (pt. 4)

This short series of posts features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success.

Night of the Big Heat (Terence Fisher, 1967)

The Asphyx (Peter Newbrook, 1973)

Night of the Big Heat (Terence Fisher, 1967)

The Asphyx (Peter Newbrook, 1973)

Tuesday, April 07, 2009

Georges Sorel - Reflections On Violence (pt. 2)

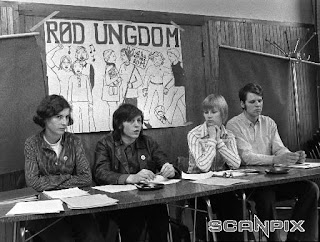

Reading Sorel's 'Reflections On Violence' I found myself wondering whether Mayhem's Øystein "Euronymous" Aarseth was aware of Sorel's thought. After all, Aarseth was a member of Rød Ungdom, a Marxist-Leninist youth movement. It is not impossible that Aarseth made acqaintance with Sorel's work, which was a formative influence on Lenin's doctrines.

Reading Sorel's 'Reflections On Violence' I found myself wondering whether Mayhem's Øystein "Euronymous" Aarseth was aware of Sorel's thought. After all, Aarseth was a member of Rød Ungdom, a Marxist-Leninist youth movement. It is not impossible that Aarseth made acqaintance with Sorel's work, which was a formative influence on Lenin's doctrines.Did Aarseth envisage the Black Metal Inner Circle as a revolutionary vanguard? Did he see the Inner Circle as a restricted, delimited group bound together in fervent solidarity? As an elite locked in a Manichaean struggle with modern Norwegian society? Wasn't his Satanism a violent, mythology which extolled fire-raising as adventurous, glorious, superior?

Perhaps a closer examination of Rød Ungdom is in order.

Rød Ungdom had its origins in the protest movements of the 1960s. Rød Ungdom was intended be a recruitment source for the radical Arbeidarklassen Party (Working Class Party). In the 1960s, Rød Ungdom organized student strikes, squats and study circles. They produced a daily newspaper, and ran a publishing house and a record company. Furthermore, the youth movement organized solidarity work for Vietnam, Palestine and Afghanistan. In the 1970s, Rød Ungdom radicalized ideologically, coming under the influence of Maoism as practiced in tyrannies such as China, Albania and Cambodia. Under this influence, the youth movement came to resemble a political sect in which assent to the party line was enforced with an iron fist. The party line decreed that homosexuality would disappear under Socialism. Rød Ungdom was suspected of being involved in terrorist attacks. Certainly, Rød Ungdom was a restricted, delimited group bound together in fervent solidarity and locked in a violent, Manichaean struggle with contemporary Norwegian society.

However, when Aarseth joined Rød Ungdom in the 1980s, the organization had begun to lose its ideological faith. China, Albania and Cambodia were not anymore inspiring examples, but were gradually coming to be seen as the depressing bureaucratic, tyrannies that they were; and masculine domination in the party was coming under feminist critique. What's more the party organization itself had become sclerotic, and the cadre demoralized and out of touch with the Zeitgeist. When the youth movement celebrated its 20th anniversary in 1983, the leader of Rød Ungdom declared: "A correct line for a development of Red Youth in 1980s has to take into account that the situation around Marxist-Leninist movement has changed. The youth revolts of the 1970s are a matter of the past past. The optimistic view of the future that characterized the 1970s has evaporated. The new situation forms the basis for pessimism and individualization among teenagers. To recruit young people to a revolutionary movement is far more difficult than before. To win support for socialism is the way much more difficult than in the early 1970s. "

However, when Aarseth joined Rød Ungdom in the 1980s, the organization had begun to lose its ideological faith. China, Albania and Cambodia were not anymore inspiring examples, but were gradually coming to be seen as the depressing bureaucratic, tyrannies that they were; and masculine domination in the party was coming under feminist critique. What's more the party organization itself had become sclerotic, and the cadre demoralized and out of touch with the Zeitgeist. When the youth movement celebrated its 20th anniversary in 1983, the leader of Rød Ungdom declared: "A correct line for a development of Red Youth in 1980s has to take into account that the situation around Marxist-Leninist movement has changed. The youth revolts of the 1970s are a matter of the past past. The optimistic view of the future that characterized the 1970s has evaporated. The new situation forms the basis for pessimism and individualization among teenagers. To recruit young people to a revolutionary movement is far more difficult than before. To win support for socialism is the way much more difficult than in the early 1970s. "Interestingly, the demoralization of Rød Ungdom was inspiring for Aarseth. He seized on the bleak, repressive nature of the Chinese, Albanian and Cambodian regimes and transvaluated them in a perverse manner. From an interview with Aarseth:

"I know you’re interested in communism. Have you been to any communist countries, if yes, what have been your emotions about it?

"I know you’re interested in communism. Have you been to any communist countries, if yes, what have been your emotions about it?I’ve been very interested in communism for a while, especially the extreme countries like Albania, Kampuchea, North Korea and so on. I have to say that I have studied so much that I know that real communism would be the best possible system, BUT as I HATE people I don’t want them to have a good time, I’d like to see them rot under communist dictatorship. Ceausescu was great, we need more people like him, Stalin, Pol Pot too. I’ve been to Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia in the (good) old days, and was about to go to Albania, although it didn’t turn out. Poland was quite all right, but it could have been even MORE gray and depressing. I like secret police, cold war and worshiping of dictators. I like bugging and spying on people, torture chambers in police stations and that people suddenly “disappear”."

Here, Aarseth seems to exalt the absence of those Socialist myths which present life in Leninist tyrannies as adventurous, glorious and superior; and for Aarseth this decisive absence of myth is more perversely joyful than the Socialist myth itself. The absence of Socialist myth is presented as a superior coldness, an adventurous grayness, a glorious depression. Aarseth's transvaluation of the withered Leninist ideology echoes Bataille, who wrote in 1947: "... the absence of myth is also a myth: the coldest, the purest, the only true myth."

Notwithstanding Aarseth's perverse transvaluation of bleakness and repression, it seems likely that the withered husk of Socialist myth did not have a lasting allure for him. With his Black Metal band Mayhem, he replaced that husk by another myth, a violent, joyful mythology which extolled fire-raising, cannibalism and sodomy as adventurous, glorious, superior: Satanism.

What the general strike was to Sorel's vicious Socialism, images of burning churches were for Black Metal. Specifically, the photographic images on Fantoft stave church in ashes were, to paraphrase Sorel "... a body of images which, by intuition alone, and before any considered analyses are made, is capable of evoking as an undivided whole the mass of sentiments which corresponds to the different manifestations of war undertaken by [Black Metal] against modern society." Wikipedia mentions that members and fans of the Norwegian black metal scene claimed responsibility for inspiring (and perpetrating) over 50 arsons directed at Christian churches between 1992–1996.

The so-called Black Metal Inner Circle functioned as a revolutionary vanguard for Aarseth Satanist myth, as an organization of the most vigorous elements of the nascent Black Metal scene bound together in fervent solidarity. Like a Sorelian, Leninist elite, the Black Metal Inner Circle hoped to provoke the staid Norwegian society to engage in a brutal Manichaean struggle.

And like Sorel, Aarseth wanted his enemies to be self-confident, unashamed, brutal:

"From what we have heard there are extreme, fundamentalist Christians planning actions against us, which we think is great. We want to see Christians become militant. We hate to see the born again Christians going around being nice to the whole world. That's extremely annoying. We want so see Christians with weapons coming here to kill us. That's what we want."

However, where Sorel was passionately confident in Socialism's ultimate triumph in the cataclysmic war on the bourgeoisie, Aarseth was under no such illusions. On the contrary, Aarseth appears to have been passionately confident that his Black Metal insurrection would meet a tragic end. As I have written before (here, here and here), much of Aarseth's extremism can be understood as a desire to provoke the Norwegian social-democrat utopia into denying him the right to exist.

However, where Sorel was passionately confident in Socialism's ultimate triumph in the cataclysmic war on the bourgeoisie, Aarseth was under no such illusions. On the contrary, Aarseth appears to have been passionately confident that his Black Metal insurrection would meet a tragic end. As I have written before (here, here and here), much of Aarseth's extremism can be understood as a desire to provoke the Norwegian social-democrat utopia into denying him the right to exist.In this tragic desire, Aarseth's Satanism reveals itself as a myth which points towards death, which is the absence - the deathlike silence - of all myths.

Sunday, April 05, 2009

Shock Xpress - Home Grown British Crud (pt. 3)

This short series of posts features trailers of British horror films mentioned in an article in the second Shock Xpress book, 'For Adults Only! Home Grown British Crud, 1954-1972', by Mike Wathen. The article examines British horror films made by producers hoping to emulate Hammer's success.

Corridors of Blood (Robert Day, 1958)

Island of Terror (Terence Fisher, 1966)

Corridors of Blood (Robert Day, 1958)

Island of Terror (Terence Fisher, 1966)

Friday, April 03, 2009

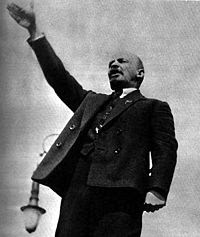

Georges Sorel - Reflections On Violence

I

IGeorges Sorel's 1908 book 'Reflections On Violence' is an ugly, hate-filled book.

The author was a socialist war monger. He harbored a ferocious desire for violent class warfare and apocalyptic revolution. In fact, Sorel was so belligerent that he consistently used the word 'peacemaker' in a pejorative sense. 'Reflections On Violence' is seething with vituperative rhetoric against those social democrat politicians who wanted to decrease socio-political tensions in pre-WWI France.

The terrorist doctrines expounded in 'Reflections On Violence' were a decisive influence on the two most bloodthirsty ideologies of human history: fascism and Leninism. Mussolini said: 'I owe most to Georges Sorel. This master of syndicalism by his rough theories of revolutionary tactics has contributed most to form the discipline, energy and power of the fascist cohorts.' Thus, the author bears a part of the responsibility for the millions of deaths caused by the totalitarian regimes of the interbellum which were based on these ideology. Even if Sorel's part of the responsibility is small, it is still too great.

Thankfully, the historical role of these murderous regimes is played out. Why not consign Sorel's book to the place where it belongs - the dustheap of history? Why read the book at all?

I myself read the Sorel's 'Reflections On Violence' because its theory of social renewal brought about by an vanguard through the use of a violent myth formed an antecedent to the activities of dissident Surrealists in the mid-nineteenthirties. Sorel's thought contributed to the formation of Acéphale, a secret society created by Georges Bataille and others.

II

IIFor Sorel, the highest good is aggressive action performed with a sense of impersonal consecration to the ends of a restricted, delimited group bound together in fervent solidarity and impelled by a passionate confidence in its ultimate triumph in some cataclysmic encounter.

Sorel wanted society to be a Manichaean struggle between the poor and rich classes. In his view, a socialist revolution could only be brought about by instilling into the working class a hatred of the bourgeoisie, not just hidden rancor and bitterness but open aggression. And rather than a middle class willing to compromise and negotiate, Sorel wanted the bourgeoisie to be self-confident and unashamed of their privileged situation. Why? Because only if the ruling class was unafraid to govern brutally, could the social tensions be maintained which instill vengeful revolutionary fervor in the proletariat. Parliamentarian democracy, philanthropy and humanitarianism were dangerous because they might pacify the proletariat and thereby prevent socialism fulfilling its historical role.

To inspire revolutionary passion in the proletariat, Sorel proposed that "...use must be made of a body of images which, by intuition alone, and before any considered analyses are made, is capable of evoking as an undivided whole the mass of sentiments which corresponds to the different manifestations of war undertaken by Socialism against modern society." In order for socialism to succeed, it was necessary to inspire the proletariat with a mythology which extolled revolutionary violence as adventurous, glorious, superior. For Sorel, the myth which which was to enthrall the working class, was the general strike. The general strike, which Sorel conceived of as a complete catastrophe of violence, enclosed all the strongest inclinations of the working class and all its anticipations of the future; it gave "...an aspect of complete reality to the hopes of immediate action by which, more easily than by any other method, men can reform their desires, passions, and mental activity."

These myths were to be inspired in the proletarian masses by an revolutionary ideological elite. Basing himself on the history of the Catholic church, 'Reflections On Violence' had declared that "... the syndicates must search less for the greatest number of adherents than for the organization of vigorous elements; revolutionary strikes are excellent for effecting a selection by weeding out the pacifists who would spoil the elite troops."

From Edward A. Shils' excellent introduction: "Sorel's ethic is the ethic of a political sect living in the midst of a continuous crisis, with all the stress on purity and all the fear of contamination by the affairs of this world which mark the sect. It is the ethic of crisis, and it is of a piece with the expectation of an ever deepening crisis which is resolved ultimately only by an apocalyptic transformation in which everything is totally changed."

III

IIIIn 1936 Georges Bataille created a secret society called "Acéphale" - Headless. Members were Georges Ambrosino, Pierre Klossowski, Patrick Waldberg. Probable members were Michel Leiris, Jacques Chavy (a sociologist, translator of Max Weber), René Chenon, Henri Dubief (a historian), Pierre Dugan, Dussat, Jean Dautry and Colette Peignot. Whether Roger Caillois was a member is disputed. Psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan was aware of Acéphale's existence and purposes, but in all probability not a member. Acéphale's members were well aware of Sorel's doctrines. Both Georges Bataille and Roger Caillois mention 'Reflections On Violence'.

Like Sorel's mythico-political sects, Acéphale was a restricted, delimited group, into which one one was ritually initiated and whose members were sworn to secrecy. The group was bound together by the performance of rituals, such as the commemoration of the beheading of Louis XVI on the Place De La Concorde on the 21st of January.

Acéphale is most notorious for a violent ritual, albeit a ritual that was never performed. Acéphale's ultimate goal was to enact a sacrifice of one of it's members. "There was another idea, hatched by Bataille, that the action of a group could be fully efficacious only if the initial pact of alliance among it's members was truly irremediable. And he was convinced that to bind their energies together, it was necessary to perform a human sacrifice. (...) I am not at all sure what transpired with regard to this projected human sacrifice. What is clear, though, is that it was easier to find a volunteer victim than a sacrificer, and so things went no further" (Caillois). The activities of Acéphale were directed towards a total transformation of society. Through the mediation of the sacrificial victim a means of communication would be established through not only between the members of the secret society, but also with society. Through this mythico-political act, social life would be stimulated and society reinvigorated. Human desires, passions, and mental activity would be reborn.

The activism of Acéphale must be seen in the light of the great political crisis of the interwar period: the rise of fascism. A fanatic struggle against fascism dominated Bataille's political life from the mid-nineteenthirties onwards. In September-October 1935, Bataille instigated Contre-Attaque, which can be seen as an anti-fascist movement related to Surrealism. Contre-Attaque was "virulently hostile to any tendency, whatever form it takes, that harnesses the Revolution to the advantage of ideas of nation or country." Acéphale was created when the Contre-Attaque fell apart, in the spring of 1936. The sacrifice that was at the center of Acéphale, should be seen as a strategy which was to bring about the triumph of Bataille's sacrificial Surrealism over National Socialist and fascist Caesarisms. Bataille's conception of sacrificial death as a tragedy was opposed politically to fascism, which denies what death is, turning it into a glamorous patriotic solution. Acéphale was a revolutionary ideological elite - but an elite of Surrealism, not of Socialism.

Like the political sects of Sorel, Acéphale was focused on violent action performed with a sense of impersonal consecration to the ends of a restricted, delimited group bound together in fervent solidarity and impelled by a passionate confidence in its ultimate triumph in some cataclysmic encounter.

When Surrealism proved to be unable to stem the tide of fascism and the triumph turned into a debacle, Bataille turned inwards. Mytho-political activism was replaced by inner experience.

Labels:

Books,

Georges Bataille,

Georges Sorel,

Mayhem,

Roger Caillois

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)