The first Shock Xpress book contains an interview with film director Joe Dante, conducted by noted critic Kim Newman. Here are some trailers of films mentioned in the interview.

Piranha (Joe Dante, 1978)

The Howling (Joe Dante, 1981)

Sunday, November 30, 2008

Friday, November 28, 2008

Georges Bataille's House in Vézelay

When I took William S. Burrough's "Ah Pook Is Here" out of my book cupboard to write the post about the Ghäst/Yoga Split, a photograph that I had forgotten about fell out. It is a photograph of Georges Bataille's house in the village of Vézelay, France.

In Le Coupable, Bataille describes his first night in the house:

In Le Coupable, Bataille describes his first night in the house:

"Arriving from Paris we entered the house, net curtains of black crêpe were drying on the trees in the sunny garden. This gloomy 'omen' was heart rending (reminding me of the long black streamers of [Innsbruck] presaging my misfortune). The first day we slept at the house, there was a lack of light in the kitchen were we dined. As night fell, the wind accompanying the storm reached an unprecedented violence, the trees in the garden were shaken like rags and twisted in the roaring of the wind. Night finally fell and the lights went out in the whole house. In the darkness I found a Christmas candle and some matches. After a while in the darkness, light finally returned.

These slight difficulties comforted and even seduced me. The calm in the storm had the strongest meaning in my life: the torment coming from the outside had calmed me down. I was afraid of nothing, it seemed to me, which might come from my deep depression."

In Michel Surya's excellent biography of Bataille, we find a description of the interior of the house:

"The house was basic and falling to pieces: a dark, narrow corridor crossed its whole depth. It first led to a dining room, then to a kitchen with a stone sink. Between them, a steep staircase led to the first and only upper floor. The landing led to two bedrooms, which were directly above and the same size as the rooms on the ground floor. One looked onto the road and the other Bataille later made his office, since the view was magnificent, overlooking a narrow terraced garden (through lack of space, Vézelay was constructed by superimposition) and, beyond it, the valley. No stove (only fireplaces), no running water (a pump), no bathroom".

Bataille first moved to the Vézelay house in March 1943, staying there until October. He moved to that house again in 1945 until 1949, when he moved to Carpentras. He was also buried in Vézelay, in 1962, in a small cemetery at the summit of Vézelay hill.

In Le Coupable, Bataille describes his first night in the house:

In Le Coupable, Bataille describes his first night in the house:"Arriving from Paris we entered the house, net curtains of black crêpe were drying on the trees in the sunny garden. This gloomy 'omen' was heart rending (reminding me of the long black streamers of [Innsbruck] presaging my misfortune). The first day we slept at the house, there was a lack of light in the kitchen were we dined. As night fell, the wind accompanying the storm reached an unprecedented violence, the trees in the garden were shaken like rags and twisted in the roaring of the wind. Night finally fell and the lights went out in the whole house. In the darkness I found a Christmas candle and some matches. After a while in the darkness, light finally returned.

These slight difficulties comforted and even seduced me. The calm in the storm had the strongest meaning in my life: the torment coming from the outside had calmed me down. I was afraid of nothing, it seemed to me, which might come from my deep depression."

In Michel Surya's excellent biography of Bataille, we find a description of the interior of the house:

"The house was basic and falling to pieces: a dark, narrow corridor crossed its whole depth. It first led to a dining room, then to a kitchen with a stone sink. Between them, a steep staircase led to the first and only upper floor. The landing led to two bedrooms, which were directly above and the same size as the rooms on the ground floor. One looked onto the road and the other Bataille later made his office, since the view was magnificent, overlooking a narrow terraced garden (through lack of space, Vézelay was constructed by superimposition) and, beyond it, the valley. No stove (only fireplaces), no running water (a pump), no bathroom".

Bataille first moved to the Vézelay house in March 1943, staying there until October. He moved to that house again in 1945 until 1949, when he moved to Carpentras. He was also buried in Vézelay, in 1962, in a small cemetery at the summit of Vézelay hill.

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Shock Xpress - Freaks in the Cinema (pt. 4)

Inspired by Colin Davis' article 'Freaks in the Cinema. A Selected History' in the first Shock Xpress book.

Terror of Tiny Town (Sam Newfield, 1938)

Terror! Il castello delle donne maledette (Dick Randall, 1974)

Terror of Tiny Town (Sam Newfield, 1938)

Terror! Il castello delle donne maledette (Dick Randall, 1974)

Monday, November 24, 2008

La Taranta (pt. 3)

Ernesto De Martino's fascinating 1961 ethnography of Apulian Tarantism, 'The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism' is strongly influenced by the idealist humanism of Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce.

Ernesto De Martino's fascinating 1961 ethnography of Apulian Tarantism, 'The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism' is strongly influenced by the idealist humanism of Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce.Because of its optimist, positivist, rational, humanitarian, decent nature, one can read De Martino's ethnography in the way proposed by Roland Barthes in 'The Pleasure of Text': "The more decent, well-spoken, innocent and saccharine a story is told, the easier it is to invert it, the easier it is to blacken it, the easier it is to read it against the grain".

Reading of De Martino's ethnography against the grain is certainly easy- one can destabilize the book's idealism when it is creatively misread in a way informed by Lovecraftian paranoia and the Cthulhu mythos!

Just consider the following quotations from the chapter on the medieval origins of Tarantism:

"First of all, there is the problem of the phenomenon's origins, the period and historical climate in which tarantism came into being, with its own forms, on the ruins of the orgiastic cults and the mystery religions. In this regard, it is impossible for us to trace any useful indication of the symbolism of the taranta in the Phisiologus and medieval bestiaries, or in the prayers, spells and recipes collected by Pradel in Griechische und Süditalienische Gebete, Beschwörungen und Rezepte des Mittelalters. The same must be said for Arab writers. (...) Furthermore, in the De Venenis by Cristoforo Degli Onesti, a Florentine who taught medicine in Padua from 1379 to 1386, there is a chapter which treats De morsu tarantulae. Although this chapter appears in the index of the manuscript preserved in the National Library of Paris, [it] is missing from the text (...)".

Why is the chapter on the bite of the tarantula missing from De Venenis? Did De Martino check all Arab writers - or did he omit to mention that he found some blasphemous indications in the work of the mad one? Why did the authorities really close up the miraculous well at St. Paul's Chapel in Corso Garibaldi in Galatina in July 1959, the well to which those afflicted by Tarantism flocked every year? Doesn't the fact that Tarantism only runs in certain family point towards an Innsmouth-like atavism? And what about the 'Sanpoalari' - Southern Italian snake charmers and traveling healers? To which secrets are they privy? And why doesn't the spider which is held responsible for tarantism correspond to any arachnid of modern zoology? Is there any connection between tarantism and the spider-god Atlach-Nacha? Does the yearly cycle of Tarantism in any way correspond to the astronomical cycle of the planet Cykranosh (or Saturn, as we know it today), the planet from which this demonic deity is said to come? Do the caverns deep beneath Mount Voormithadreth, where the god resides, lead to the Apulian Monte Gargano, or even further south? What about the giant, bloated purple spiders of Leng, which are thought to be the children and servitors of Atlach-Nacha? Wasn't Tarantism mentioned in Unaussprechlichen Kulten by Von Junzt? Or was it Ludwig Prinn's De Vermis Mysteriis?

Post scriptum

Only after writing this post, I read the passages in Reza Negarestani's Cyclonopedia on Hidden Writing.

Saturday, November 22, 2008

La Taranta (pt. 2)

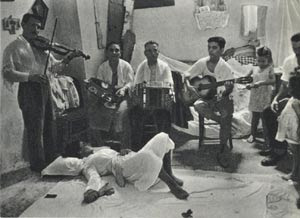

I stumbled on the documentary featured in the previous post when reading Ernesto De Martino's classic 1961 ethnography La Terra Del Rimorso (The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism). The book is the result of ethnographic research into Tarantism, conducted by an interdisciplinary team of historians, psychiatrists, medics, anthropologists and social workers. The fieldwork took place in Apulia, the state that forms the heel in Italy's boot, in the summer of 1959.

I stumbled on the documentary featured in the previous post when reading Ernesto De Martino's classic 1961 ethnography La Terra Del Rimorso (The Land of Remorse: A Study of Southern Italian Tarantism). The book is the result of ethnographic research into Tarantism, conducted by an interdisciplinary team of historians, psychiatrists, medics, anthropologists and social workers. The fieldwork took place in Apulia, the state that forms the heel in Italy's boot, in the summer of 1959.What is Tarantism? It is an affliction which the Apulians ascribe to the bite of the Tarantula spider, and which reoccurs in regularly repeating yearly cycles in those bitten. The symptoms include "...falling to the ground, a feeling of prostration, anguish, a state of psychomotor agitation with a beclouding of the sensory apparatus, difficulty in remaining standing, stomach ache, nausea and vomiting, various paresthesias and muscular pains, a heightening of sexual desire...".

The research team found out that - even though the symptoms vaguely resembled those of spider poisoning - Tarantism could be reduced neither to the bite of an actual spider nor to other causes, such as sunstrokes or psychic illness. On the contrary, in the course of the investigations Tarantism acquired the meaning of a mythical-ritual symbol, culturally conditioned in its functioning and efficacy.

The spatial and temporal distribution of 'spider's bites' made it highly unlikely that actual spiders were responsible for the phenomenon. There was an overwhelming prevalence of pubescent female participation in Tarantism, and the phenomenon afflicted certain families only. Once bitten, the victim would be affected in the summer for several years, the phenomenon obeying a strict calender. Furthermore, certain locations associated with specific Saints - such as the town of Galatina, of which the St. Paul church is featured in the film - provided immunity from the spiders' bite.

The spider which was held responsible for tarantism was a mythical creature which did not correspond to any arachnid of modern zoology. Instead, the Taranta assembled the characteristics of several different species of spider into a mythical whole. Different colors were attributed to the spiders - principally red, green and black - and the 'bite' of each respective spider caused different behaviour in the victim. Those bit by red spiders displayed martial, heroic behaviour; those bit by green spiders displayed eroticized behaviour; and those bitten by black spiders were fascinated by funerary paraphernalia. Furthermore, each color spider had its own repertoire of musical figures and dances: for example, those bitten by a green spider would only dance to a Tarantella tune associated with the green spider. Finally, the victims of the spider's bite were fascinated by pieces of cloth with the appropriate color. Thus, during the course of an exorcism different Tarantella tunes were played and different colors of clothes were given to the victim in order to determine which spider possesses her. Only the appropriate Tarantella tune, the appropriate color and the appropriate dance would cure the victim - at least for the time being, until the affliction re-occured a year later. Music serves at once as diagnosis and therapy.

The spider which was held responsible for tarantism was a mythical creature which did not correspond to any arachnid of modern zoology. Instead, the Taranta assembled the characteristics of several different species of spider into a mythical whole. Different colors were attributed to the spiders - principally red, green and black - and the 'bite' of each respective spider caused different behaviour in the victim. Those bit by red spiders displayed martial, heroic behaviour; those bit by green spiders displayed eroticized behaviour; and those bitten by black spiders were fascinated by funerary paraphernalia. Furthermore, each color spider had its own repertoire of musical figures and dances: for example, those bitten by a green spider would only dance to a Tarantella tune associated with the green spider. Finally, the victims of the spider's bite were fascinated by pieces of cloth with the appropriate color. Thus, during the course of an exorcism different Tarantella tunes were played and different colors of clothes were given to the victim in order to determine which spider possesses her. Only the appropriate Tarantella tune, the appropriate color and the appropriate dance would cure the victim - at least for the time being, until the affliction re-occured a year later. Music serves at once as diagnosis and therapy.Rather than the result of the bite of an actual spider, Tarantism was a mythical-ritual experience which was modeled on the medical symptoms of the actual bite of a poisonous spider. Examining parallels in ethnography and folklore, De Martino found structural similarities between Tarantism and Afro-Mediterranean and Afro-American (Vodou) possession cults. Furthermore, De Martino found antecedents to this religious formation in classical Greek mythology and rituals.

De Martino interprets Tarantism primarily as a form of psychological therapy. For his, the Tarantella is an exorcism, as a ritual eviction of the spider which possesses the victim. The spider symbolizes a traumatic event in the biography of the victim (specifically frustrated eros), and it is the memory of that traumatic effect which causes the affliction of Tarantism with its attendent symptoms. This memory is cast out my music, color and dance - the Tarantella. For De Martino, the symbol of the Taranta is a "mythical-ritual horizon of evocation, release and resolution of unresolved psychic conflicts (...). As a cultural model, the symbol offers a mythical-ritual order for settling these conflicts and reintegrating individuals into the group. The symbol of the taranta lends a figure to the formless, rhythm and melody to menacing silence, and color to the colorless in an assiduous quest of articulated and distinct passions, where a horizonless excitation alternates with a depression that isolates and closes off."

(A short aside on formlessness. That De Martino associates the spider with formlessness certainly struck a chord with me: for Georges Bataille, the spider was an almost formless creature, an invertebrate that is not like anything: "To declare (...) that the universe is not like anything, and is simply formless, is tantamount to saying that the universe is something like a spider or spittle." (Documents 7, 1929). The relation between Bataille's thought and formlessness is the polar opposite of the relationship between De Martino's thought and formlessness.)

Gilbert Rouget, whose 1985 ethnography "Music and Trance. A theory of the relations between music and possession" was featured before on this blog, was highly critical of De Martino's interpretation of Tarantism. Rouget writes that De Martino's analysis makes one lose sight of the most obvious aspect of Tarantism: the identification of the afflicted with the spider. Rouget: "One of the dance figures of the tarantulees - the best known - consists, as we know, in imitating the spider's movements: back to the ground, body arched to a great or lesser degree, the tarantulee moves about like a spider on all fours. One can see this very clearly in D. Carpitella's film, and the sight is striking." (Rouget is mistakingly referring to La Taranta as Carpitella's film: Carpitella merely recorded the music). Rouget reproaches De Martino for making himself an heir to a Christian tradition which abjects possession and possessing divinities and thereby misinterpreting Tarantism. Rouget: "Despite appearances, the divinity responsible for the possession is not the one that is excorcised. On the contrary, it is the divinity concerned who, by allowing the possessing person to identify with him or her, provides the means of ecxorcising the illness - real or imagined - from which the person is suffering."

Gilbert Rouget, whose 1985 ethnography "Music and Trance. A theory of the relations between music and possession" was featured before on this blog, was highly critical of De Martino's interpretation of Tarantism. Rouget writes that De Martino's analysis makes one lose sight of the most obvious aspect of Tarantism: the identification of the afflicted with the spider. Rouget: "One of the dance figures of the tarantulees - the best known - consists, as we know, in imitating the spider's movements: back to the ground, body arched to a great or lesser degree, the tarantulee moves about like a spider on all fours. One can see this very clearly in D. Carpitella's film, and the sight is striking." (Rouget is mistakingly referring to La Taranta as Carpitella's film: Carpitella merely recorded the music). Rouget reproaches De Martino for making himself an heir to a Christian tradition which abjects possession and possessing divinities and thereby misinterpreting Tarantism. Rouget: "Despite appearances, the divinity responsible for the possession is not the one that is excorcised. On the contrary, it is the divinity concerned who, by allowing the possessing person to identify with him or her, provides the means of ecxorcising the illness - real or imagined - from which the person is suffering."Whatever the case may be, De Martino's book is highly interesting for those who are interested in possession - whether for scientific reasons or because possession can function as a model for countercultural practices. In De Martino's book, possession is not the exotic practice of an exotic people in an exotic land: La Terra Del Rimorso presents ethnographic and historiographic material on a possession cult which takes place in Europe itself. What's more, Tarantism has its roots in the very soil from which Western civilization sprang: in classical Greece. We were already possessed in the cradle.

Post scriptum

Here is an indepth review of De Martino's book (link).

Thursday, November 20, 2008

La Taranta (pt. 1)

The two YouTube videos embedded below together form the 1962 documentary La Taranta, which investigates a Southern Italian possession cult: Tarantism. The film, directed by Gianfranco Mingozzi, documents this fascinating peasant religious formation in which the victims of the bite of the mythical Tarantula require a ritual exorcism of frenetic dance, music and colors.

The two YouTube videos embedded below together form the 1962 documentary La Taranta, which investigates a Southern Italian possession cult: Tarantism. The film, directed by Gianfranco Mingozzi, documents this fascinating peasant religious formation in which the victims of the bite of the mythical Tarantula require a ritual exorcism of frenetic dance, music and colors.Even if you do not speak Italian, do watch the film, for it is convulsively beautiful. In my mind, its 19 minutes assemble Luis Buñuel's 1933 documentary on the grinding poverty of Spanish peasants Las Hurdes, Herk Harvey's 1962 existential horror film Carnival of Souls and Jean Rouch's 1955 documentary on the Hauka possession cult Les Maitres Fous. The documentary was filmed in a black and white which is so funereal it is almost Xasthuresque, and its music - the famous Tarantella - is haunting. In short: my highest recommendations!

*

The next post will provide indepth material on Tarantism!

Post scriptum

Some readers of this blog might be familiar with Mingozzi's name from the 1974 nunsploitation film Flavia, la Monaca Musulmana.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Shock Xpress - Freaks in the Cinema (pt. 3)

Inspired by Colin Davis' article 'Freaks in the Cinema. A Selected History' in the first Shock Xpress book.

The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

Captive Wild Woman (Edward Dmytryk, 1943)

The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980)

Captive Wild Woman (Edward Dmytryk, 1943)

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Ghäst / Yoga - Split

The work of J.R.R. Tolkien has had an indelible influence on Black Metal culture. Many names of Black Metal bands have been derived form Tolkien's oeuvre. Christian 'Varg' Vikernes was a Tolkien aficionado, and named his one-man band Burzum, the word for "darkness" in the Black Speech of Mordor. Norwegian Black Metal band Gorgoroth is named after the plain of Gorgoroth within the mountains that cordon off Mordor from the rest of Middle-Earth. Isengard - named after the castle of evil sorcerer Saruman - is a solo project of Fenriz, the drummer of Darkthrone.

The work of J.R.R. Tolkien has had an indelible influence on Black Metal culture. Many names of Black Metal bands have been derived form Tolkien's oeuvre. Christian 'Varg' Vikernes was a Tolkien aficionado, and named his one-man band Burzum, the word for "darkness" in the Black Speech of Mordor. Norwegian Black Metal band Gorgoroth is named after the plain of Gorgoroth within the mountains that cordon off Mordor from the rest of Middle-Earth. Isengard - named after the castle of evil sorcerer Saruman - is a solo project of Fenriz, the drummer of Darkthrone.What does that mean? What does the choice of the Tolkien's oeuvre, of the literary genre of Fantasy reveal about Black Metal?

Science Fiction can be loosely defined as fiction which speculates about social effects of future technological advances. Fantasy as a genre is not oriented towards the future or technology. Fantasy constructs fictitious pre-modern (tribal or feudal) societies, and explores themes related to the history of religions, morality (good vs evil) and heterophobia (in the sense of: "fear of that which is different"). Because it is not oriented towards future societies and explores different themes, Fantasy has been compared negatively to Science Fiction. Fantasy has been called retrogressive. However, the mere fact that the fictitious societies of Science Fiction are technologically advanced and those of Fantasy are not, is in itself not enough to condemn the latter genre. Themes like the history of religions, morality and heterophobia are relevant to our society, and are highly likely to be relevant to societies of the future. Calling literature in which the drama takes place in pre-modern societies irrelevant is tantamount to calling the academic disciplines of history and anthropology irrelevant. Like all literature, good Fantasy novels can convey to us something about the human condition.

The themes of Fantasy novels are highly relevant to Black Metal. Black Metal themes such as Satanism, daemonology, paganism and black magic all indicate an interest in the history of religions. The musical genre's obsession with evil relates to questions of morality. Heterophobia finally is a hallmark of this ofttimes intolerant, hateful music.

One might say that without the Fantasy influence, Black Metal wouldn't be Black Metal but another genre entirely.

Nevertheless, I feel that such a statement is a little bit too facile. And anyway, it is interesting to speculate what Black Metal might have sounded like, if classic Norwegian Black Metal bands had not been influenced by Tolkien, but by other literature. What would it have sounded like if the work of William S. Burroughs had played the role that Tolkien's oeuvre played?

Nevertheless, I feel that such a statement is a little bit too facile. And anyway, it is interesting to speculate what Black Metal might have sounded like, if classic Norwegian Black Metal bands had not been influenced by Tolkien, but by other literature. What would it have sounded like if the work of William S. Burroughs had played the role that Tolkien's oeuvre played?What if the landscape of Mordor was replaced by a landscape of "swamps and garbage heaps, alligators crawling around in broken bottles and tin cans, neon arabesques of motels, marooned pimps [screaming] obscenities at passing cars from islands of rubbish"?

What is orcs and elves and hobbits were replaced by "followers of obsolete, unthinkable trades doodling in Etruscan, addicts of drugs not yet synthesized, pushers of souped-up Harmaline, junk reduced to pure habit offering precarious vegetable serenity, liquids to induce Latah, Tithonian longevity serums, black marketeers of World War III, excisors of telepathic sensitivity, osteopaths of the spirit, investigators of infractions denounced by bland paranoid chess players, bureaucrats of spectral departments, officials of unconstituted police states..."?

The music of two-man band Yoga might provide the beginning of an answer to those questions.

In an interview with the Hammer Smashed Jazz blog, one of Yoga's musicians describes the music as 1970s 'Berlin School' Kraut Rock Electronica (Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream) recorded with the fuzzed out, cold, hollow-sounding, thin, raw, completely blown out and in the red recording style prevalent in underground Black Metal. "The dirtier and [the more] desperate the sound, the more otherworldly and distant the sounds became."

In an interview with the Hammer Smashed Jazz blog, one of Yoga's musicians describes the music as 1970s 'Berlin School' Kraut Rock Electronica (Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream) recorded with the fuzzed out, cold, hollow-sounding, thin, raw, completely blown out and in the red recording style prevalent in underground Black Metal. "The dirtier and [the more] desperate the sound, the more otherworldly and distant the sounds became."I'm not at all a fan of the New Agey strains of Kraut Rock. Tangerine Dream's universally acclaimed classic, the 1974 album Phaedra, bores me: entirely conventional, soothing, feeble music. I enjoy Yoga's music exactly because it uses New Agey Kraut Rock in a way William S. Burroughs proposed to use the voice of Alabama pro-segregation politician George Wallace. Burrough's essay 'The Electronic Revolution' contained these instructions: "Take a recorded Wallace speech, cut in stammering coughs sneezes hiccups snarls pain screams fear wimperings apoplectic stutterings slobbering drooling idiot noises sex and animal sound effects and play it back in the streets subways stations parks political ralleys." Where Burroughs advises to garble Wallace's conservative harangues with the aural excretions of the human body, Yoga destructurates Kraut Rock's conservative side with sonic detritus, hellish wailing, ruinous distortion, tape hiss, drop outs, intense squalls of blackened noise, sinister drones, constant churning and warbling.

The resulting music evinces the hallucinatory quality of Burroughs work: a fantastic, nightmarish merging of the rectums of early Coil, Goblin and Xasthur, an unendurably ragged, malodorous delight.

Post scriptum

The split cd under review contains 8 tracks by Yoga and two by Quebecois Doom Metal band Ghäst. The Ghäst tracks earn sympathy by using samples from Amando de Ossorio's 1971 horror film La Noche Del Terror Ciego (aka Tombs of the Blind Dead), but are otherwise instantly forgettable. The Yoga tracks were released on an extremely limited cassette (only 50 copies!) before being released in its current form (limited to 250 copies)

Friday, November 14, 2008

Shock Xpress - Freaks in the Cinema (pt. 2)

Inspired by Colin Davis' article 'Freaks in the Cinema. A Selected History' in the first Shock Xpress book.

The Mutations (Jack Cardiff, 1974)

The Sentinel (Michael Winner, 1976)

The Mutations (Jack Cardiff, 1974)

The Sentinel (Michael Winner, 1976)

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Vodou, Art and Mysticism from Haiti

Do not visit the exhibition 'Vodou, art and mysticism from Haiti' at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. I did, on November 8th 2008, and still I sleep uneasily.

Do not visit the exhibition 'Vodou, art and mysticism from Haiti' at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. I did, on November 8th 2008, and still I sleep uneasily.Do not visit that exhibition when it moves to the Museum of World Culture in Göteborg, Sweden. The exhibition starts innocently enough, presenting Vodou's most acceptable, folkloric face. It starts politically correct enough, appealing to the emancipatory meaning of Enlightenment in presenting the Haitian religion as a weapon in the struggle against French and American colonial domination. It starts nicely enough, in an Apollonian mode, presenting the Lwa - Vodou's spirits - as the contemporary equivalents of the gods of ancient Greece, exotic and slightly naive, weird but safe. But then you turn a corner, and through a dimly lit passageway you are led to two darkened rooms which reveal a world which has nothing to do with our solid, daylight-filled and clear-headed world. You are led into the ominous world of the secret societies known as Bizango. There, your nerves will start to fray, as did mine.

Do not visit the exhibition when it appears at the Etnologisches Museum in Berlin. Some paragraphs in Alfred Métraux' classic 1959 ethnography Voodoo in Haiti should provide ample warning:

Do not visit the exhibition when it appears at the Etnologisches Museum in Berlin. Some paragraphs in Alfred Métraux' classic 1959 ethnography Voodoo in Haiti should provide ample warning:"The people designated by [the name Bizango] are sorcerers who (...) have joined secret societies whose members, united by the crimes they have committed together, give each other help. The [Bizango] derive material benefits from membership - wealth and all its trappings - a fine house, luxurious cars and a trip to France - though these considerations are secondary to the satisfaction of returning evil for evil, and of 'eating people' during nocturnal expeditions. (...)

Countless stories can be heard about [the Bizango] really belong to the province of the fairy tale, but it seems likely that certain people sometimes do band together, in secret, to practice sorcery or to use the popular belief in sorcerer societies to sow terror around them. Proof that the matter is not wholly a question of superstition is to be found in the passports of the [Bizango], confiscated in humfo [voodoo temples] or handed over to curés by repentant voodooists.

The most sinister fantasies of a kind sure to capture popular imagination have been centered on the 'red sects'. Hideous or grotesque aspect, weird dress, obscene and bloody ceremonies, gratuitous cruelty, weird dress, obscene and bloody ceremonies, gratuitous cruelty - there is no conceivable trait that is not attributed to them provided it is sufficiently repulsive and odious. (...) "

And please do not visit it in Bremen's Überseemuseum, in Germany, as the three rooms in the exhibition dedicated to the Bizango societies contain many frightening artifacts, especially paquets, statues and mirrors (see them on this excellent Flickr slideshow).

And please do not visit it in Bremen's Überseemuseum, in Germany, as the three rooms in the exhibition dedicated to the Bizango societies contain many frightening artifacts, especially paquets, statues and mirrors (see them on this excellent Flickr slideshow).The paquets ('parcels') are a special kind of talisman, made of wallets or bottles (sometimes big onion-shaped bottles) wrapped in cloth or silk studded with sequins and adorned with frills. Some of the Bizango paquets on displays had human skulls as stoppers. These paquets, which contain the flesh of a sacrificed 'curly cock' mixed with vegetable substances, have the power of 'heating' or exciting the Lwa; but they also have the power of raising goosebumps on the skin of the museum's visitors.

There is a veritable army statues on display. They are life-size, made of black and red cloth filled up with unknown materials, and adorned with ropes, metal chains and little oxidation-stained mirrors. The statues represent the spirits which rule the Bizango sects, and especially the trinity of Kaifou, Gran Bwa and Simityè (Crossroads, Great Forest and Cemetery). Their eyes - most white, others red, some reflecting - rest heavily on the visitor to the exhibition. They rest all the more heavily when the realization dawns on the visitor that human skulls are sown into the head of these statues; thereafter, their eyes seem to be neither seeing nor dead, neither living nor blind.

But the mirrors on display are the most disconcerting of all exhibits. They are ornate, 19th century mirrors, stained by oxidation, weathered by the passage of time. Their gilded frames are elaborated with rusty chains and sinister woodcuts of snakes and daemons. At the top of a huge circular mirror, a primitive Lucifer winks to the visitor. These mirrors are used to call forth the spirits of Bizango; their reflective surface forms the permeable boundary between this world and a nightmarish Otherworld. As philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty noted, mirrors "...change things into spectacle and spectacle into things; myself into another and another into myself...". I trembled at seeing myself in these mirrors, sensing they dissolved the boundaries between self and Bizango.

In his ethnography of Vodou, Métraux writes that - when seen up close - the religion of Haiti does not have the morbid and hallucinatory character which books have given it. That black legend, writes Métraux "..belongs to the colonial period when it was the fruit of hatred and fear. Man is never cruel and unjust with impunity: the anxiety which grows in the minds of those who abuse power often takes the form of imaginary terrors and demented obsessions. He treated him like a beast of burden but dreaded the occult power which he imputed to him. And the greater the subjugation of the Black, the more he inspired fear; that ubiquitous fear which shows in the records of the period and which solidified in that obsession with poison which, throughout the eighteenth century, was the cause of so many atrocities. Perhaps certain slaves did avenge themselves on their tyrants in this way - such a thing is possible and even probable - but the fear which reigned in the plantations had its source in deeper recesses of the soul: it was the witchcraft of remote and mysterious Africa which troubled the sleep of the people in 'the big house'."

In his ethnography of Vodou, Métraux writes that - when seen up close - the religion of Haiti does not have the morbid and hallucinatory character which books have given it. That black legend, writes Métraux "..belongs to the colonial period when it was the fruit of hatred and fear. Man is never cruel and unjust with impunity: the anxiety which grows in the minds of those who abuse power often takes the form of imaginary terrors and demented obsessions. He treated him like a beast of burden but dreaded the occult power which he imputed to him. And the greater the subjugation of the Black, the more he inspired fear; that ubiquitous fear which shows in the records of the period and which solidified in that obsession with poison which, throughout the eighteenth century, was the cause of so many atrocities. Perhaps certain slaves did avenge themselves on their tyrants in this way - such a thing is possible and even probable - but the fear which reigned in the plantations had its source in deeper recesses of the soul: it was the witchcraft of remote and mysterious Africa which troubled the sleep of the people in 'the big house'."The exhibition 'Vodou, art and mysticism from Haiti' proves that Voodoo - or the Bizango cult in any case - does have a hallucinatory and morbid character. The sleep of the people in 'the big house' was not troubled for nothing.

I still sleep uneasily.

Monday, November 10, 2008

Shock Xpress - Freaks in the Cinema (pt. 1)

Saturday, November 08, 2008

0))) Presents... Pentemple

I

IPentemple: a minotauric music, a composite of the modernist and the archaic, an unholy assemblage of droning Minimalism and blackened Doom Metal.

As if Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s etchings of imaginary dungeons had been re-imagined by Brutalist architects: the Baroque intricacies of the stairs and arches, beams, wheels, cables and grates, replaced by colour-depleted and crumbling concrete textures and depressively repetitive angular geometries.

As if the noxious smog that hangs over Throbbing Gristle's desolate, sickly late-1970s-England had descended upon the serene pastoral scenery of Ernst Jünger's Auf den Marmörklippen: fog mixed with industrial smoke and fumes suffocating the bucolic composite landscape that Jünger assembled from the rocks around the Capo Gallo lighthouse at Mondello, from Corfu, from the Rodino valley of Rhodes, from a road which runs along Lake Constance, from the Acropolis and from the cliffs of Rio de Janeiro.

As if Theodor Kittelsen's 1896 illustration "Musstad" ("Decrepitude"; reproduced in the interior sleeve art of Burzum's 1996 album Filosofem) wasn't a naive, Neo-Romantic illustration of a fairytale but a sickening premonition of the extermination camps of the twentieth century.

As if an nth generation washed-out Betamax videocassette tape of Mario Bava's 1961 Viking epic Gli Invasori was restructured by Jack Smith as a trashadelic film experiment: filtered long shots of faux-Norwegian landscapes, medium shots of Viking Flaming Creatures applying corpse paint, flickering shapes and formless cathode tube static, overexposed into fogginess, pulsing and throbbing, spinning and shifting.

II

IIPentemple documents two Sunn 0))) concerts in Australia, which were part of their May 2007 Pacific Rim tour. The collective was made up from disparate elements: besides Californians Greg Anderson and Stephen O'Malley, the line-up included Dutchman Thomas Nieuwenhuizen (Moog-fiddling Punk), the Australian Oren Ambarchi (Jewish mystic turned sonic investigator), the Hungarian Attila Csihar (onetime heir to the throne of Dead in Mayhem), and finally the Australian Sin Nanna (misanthropic dweller of the Tasmanian rainforest, demented genius behind outsider Black Metal band Striborg).

From this Unholy gathering a collective, simultaneously improvised music emerged: an immense rumbling cloud-like drone, constantly churned up by Csihar's growls, chants, and whispers, and by Sin Nanna's almost Free Jazz drumming. Listening to the musicians communicate musically, one hears delirious concentration, brutal sensitivity and blind imagination. The resultant raw material (raw in all senses of the word) was recorded live to a 24-track/multi-track, and it was subsequently operated into consistency or consolidation by Ambarchi.

Mysterious and electrifying, Pentemple has been in semi-constant rotation ever since I bought it five days ago. It works much better than Gravetemple's "The Holy Down", a live album which documents a July 2006 collaboration of O'Malley, Anderson and Ambarchi in Tel Aviv, Israel. Compared to that album, Pentemple is more varied: it arranges decades of Doom and Black Metal and (Un-)Holy Minimalism into a single moonsick landscape of dissonance. The interior of the sound is an interior environment which an intrepid listener may explore at his own peril.

In fact, one might call Pentemple's music an aural form of Land Art. Like Land Art, Pentemple offers simplicity of form and concentrates on the (sonic) materials themselves. Both Land Art and Pentemple have an affinity with Minimalism. Land Art and Pentemple employ cthonic materials, abject materials traditionally considered "un-artistic" or "worthless" (earth and Metal). The fact that nearly all of the first wave of Land Artists were male, and worked in a manner that was both invasive and transformative, gave the art form a reputation for being driven by testosterone; likewise, Metal is strongly associated with masculinity. Land Art combines the archaic and the modern by raising paleolithic monuments to adress the very contemporary issue of an environment destroyed by technology; Pentemple harnesses the power of electricity to make an image flash up of the archaic past as a maze in which one would lose one's way.

"In the heart of the labyrinth, Theseus has no thought of return, he is not worried about getting out, he anxiously desires the Minotaur." (sourced here).

III

Here are three YouTube videos of the Pentemple concert at the HiFi Bar in Melbourne on May 9, 2007. The poor sound of the videos in no way reflects the aural majesty of the album.

*

Thursday, November 06, 2008

Shock Xpress - Stephen Gallagher (pt. 5)

The final post in a series inspired by an article in the first Shock Xpress Book, in which horror writer Stephen Gallagher lists his 10 favorite horror films.

La Belle et la Bête (Jean Cocteau, 1946)

Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

La Belle et la Bête (Jean Cocteau, 1946)

Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

Tuesday, November 04, 2008

Torture of a Hundred Pieces (pt. 2)

I

IIn his excellent biography of Georges Bataille, Michel Surya situated Bataille's ecstatic contemplation of photographs of the Torture of a Hundred Pieces in the Christian tradition of identification with the suffering of the Messiah. Thus, Bataille's meditative mimesis with the victim is contextualized in the history of (theological and philosophical) thought. Of course, this is perfectly appropriate for a book which aims to be an 'intellectual biography'.

In the previous post of this series, I hypothesized that it is also possible to situate Bataille's meditative mimesis in the context of the literary and aesthetic history of Black Romanticism. This enables me to explore the context even further, examining the historical backgrounds of this literary movement and its relevance to Bataille's grisly ecstasies.

II

The development of Romanticism occurred in the context of the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and Colonization. The socio-cultural, political and economic changes that these historical developments entailed, informed the literary genre. Colonial expansion brought about encounters between colonialists and foreign peoples and places, and Romanticism as a genre arose partly as a response in writing to such encounters.

In the process of colonial expansion, two diametrically opposed but interconnected views of foreign peoples emerged. In one of these a pastoral ideal, which earlier generations had placed in a mythical or classical past, in a real, was situated in an exotic yet visitable landscape. A salient example of this tendency is Gaugain's representation of Tahiti as an earthly paradise. In the other, the exotic people are savage: they transgress all symbolic boundaries, especially the boundaries imposed by utilitarianism, morality and rationality. That, according to Michael Taussig's 1986 ethnography "Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man. A Study in Terror and Healing", Colombian colonialists saw Amazonian Indians as violent and cruel cannibals, can be seen an example of this second tendency. As Taussig's ethnography shows, the two tendencies are not mutually exclusive; on the contrary, they are intertwined. The exotic people are a savage anti-self of the colonist, at once attractive and repulsive. This anti-self is not well-defined and clear-cut, but swathed in what Taussig calls 'epistemic murk': it is the unclear, murky nature of the wildness ascribed to exotic people in colonial fabulation that gave their 'otherness' such a powerful, obsessing hold on the imagination of the colonists.

Black Romanticism used this contradictory view of exotic people for its own perverse purposes. In this literary genre, foreign peoples and places were painted as exotic, erotic, attractive and repulsive. Mario Praz's classic 1930 book on Black Romanticism, The Romantic Agony, provides many examples of this.

III

In 1905, China was not a colony in the strict sense of the word. Nevertheless, China and her people were very much under Western domination following the repression of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, and several major cities were controlled by Western troops. The Western view of China and the Chinese was undoubtedly strongly influenced by 'murky' colonial constructions of the colonized, exotic Other as at once attractive and repulsive.

The Chinese were at once represented as at once venerable, intelligent, cultured and aesthetically refined, and as decadent, cruel and addicted to opium. The portrait painted of the fictitious villain Fu-Manchu in Sax Rohmer's 1913 novel 'The Insidious Dr. Fu-Manchu' neatly encapsulates this bifurcated image:

"Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government—which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man."

"Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government—which, however, already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man."This attractive and repulsive Other was eroticized. A BDSM blog post on the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu: "This is classic Orientalist BDSM fantasy, a dreamworld of magic, cruelty and sensuality. The nominal heroes are such passive drips (who incidentally regard other cultures with contempt) and the nominal villains are so charismatic and powerful that ones sympathies are almost reversed 180 degrees. All of this serves as a vehicle for male and female masochistic fantasies of bondage, captivity, mind-control, same sex action, medical procedures, deathtraps and more."

In the early twentieth century, the idea that the Chinese experienced a cruel delight in exquisitely refined torture was widespread. The cruelty of the Chinese was represented by photographs of executions that were diffused through modern mass media such as illustrated journals or postcards. In this website, specialized in representations of early twentieth century Chinese torture (!), you'll find many such photographs and postcards: Faces of Death avant la lettre.

IV

In Bataille's oeuvre, one can find several instances where he appropriates colonialist discourse on the Other and transvaluates it, turning the moral structure of the colonialist view of the colonized topsy-turvy. In this sense, Bataille's take on colonialism can be characterized as carnivalesque.

One example of this strategy can be found in Bataille's Critical Dictionary, which was published in Documents, the journal which inspired this blog. In an entry in the Critical Dictionary (Documents 6, 1930) on the Hindu Goddess Kali, Bataille makes extensive use of Katherine Mayo 1927 book "Mother India". This book, though written by an American journalist, took a strong pro-colonialist stance, arguing that India was not ready for independence. It painted a sensationalistic picture of India: bloodthirsty sacrificial rites to Kali, child marriage, superstition, widow burning, young pregnancy, temple prostitution dominate Mayo's book. Bataille's Kali entry in the Critical dictionary transvaluates Mayo's blood-soaked description of Kali worship, exalting that which Mayo finds abject. In Documents, a similar strategy is applied to W.H. Seabrook's sensationalist book on Haitian Voodoo 1929 "The Magic Island".

What do we see if we situate Bataille's ecstatic contemplation of photographs of the Torture of a Hundred Pieces in the context of colonialism?

Bataille's meditative mimesis appropriates what is abjected by colonialism in Chinese culture and exalts it: the eroticized experience of a delight in exquisitely refined torture. Like the colonial construction of the Other, Bataille's position with regards to the torturer and the tortured is swathed in 'epistemic murk': he described his experience both as sadistic and as masochistic.

Bataille's ecstatic contemplation of torture is a carnival of colonialism, in which the colonial hierarchy of values is turned topsy-turvy. Western disciplining rationality is sacrificed to ostentatious Chinese cruelty, "hideous, crazed, lined with blood, as beautiful as a wasp".

Sunday, November 02, 2008

Shock Xpress - Stephen Gallagher (pt. 4)

Inspired by an article in the first Shock Xpress Book, in which horror writer Stephen Gallagher lists his 10 favorite horror films.

Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972)

Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963)

Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972)

Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)